Spain at flood risk: over a million homes stand at hazardous areas

Ten minutes were enough for the water to devastate dozens of homes in Javalí Viejo, a village in the city of Murcia. This occurred in September 2022. The residents of San Nicolás street, parallel to Ventosa Avenue, bore the brunt of it. The water flooded homes and washed away walls, furniture, and vehicles. It also swept Antonio away, whose body was found 300 meters away. “I really thought we were going to die,” says Josefa Santiago, who is still frightened. She is one of the inhabitants of the Spain at flood risk, a census elaborated in detail for the first time by elDiario.es that includes at least 1.03 million households nationwide. 4.3% of all dwellings in the country.

Source: Ministry of Ecological Transition, Cadaster

These inhabited landscapes of Spain that are living with one eye on floods and rising seas - or dangerously unaware of them - include at least 370,415 buildings, according to an elDiario.es investigation based on data from the Cadaster and the National Floodplain Mapping System. This map provides detailed access to flood-prone areas at both the street and even house-by-house level. It represents the first-ever analysis of over 12 million properties in the country (click to see the full methodology). And it unveils entire villages within the perimeter of potential fluvial flooding, as well as miles and miles of new housing developments under threat from coastal flooding.

The effects of this weekend's cold spell on the peninsula have brought back into the spotlight the damage that can be caused by flooding, which has so far left three people dead. Among the areas worst affected by the storm are Toledo, Madrid, Castellón and the south of Tarragona.

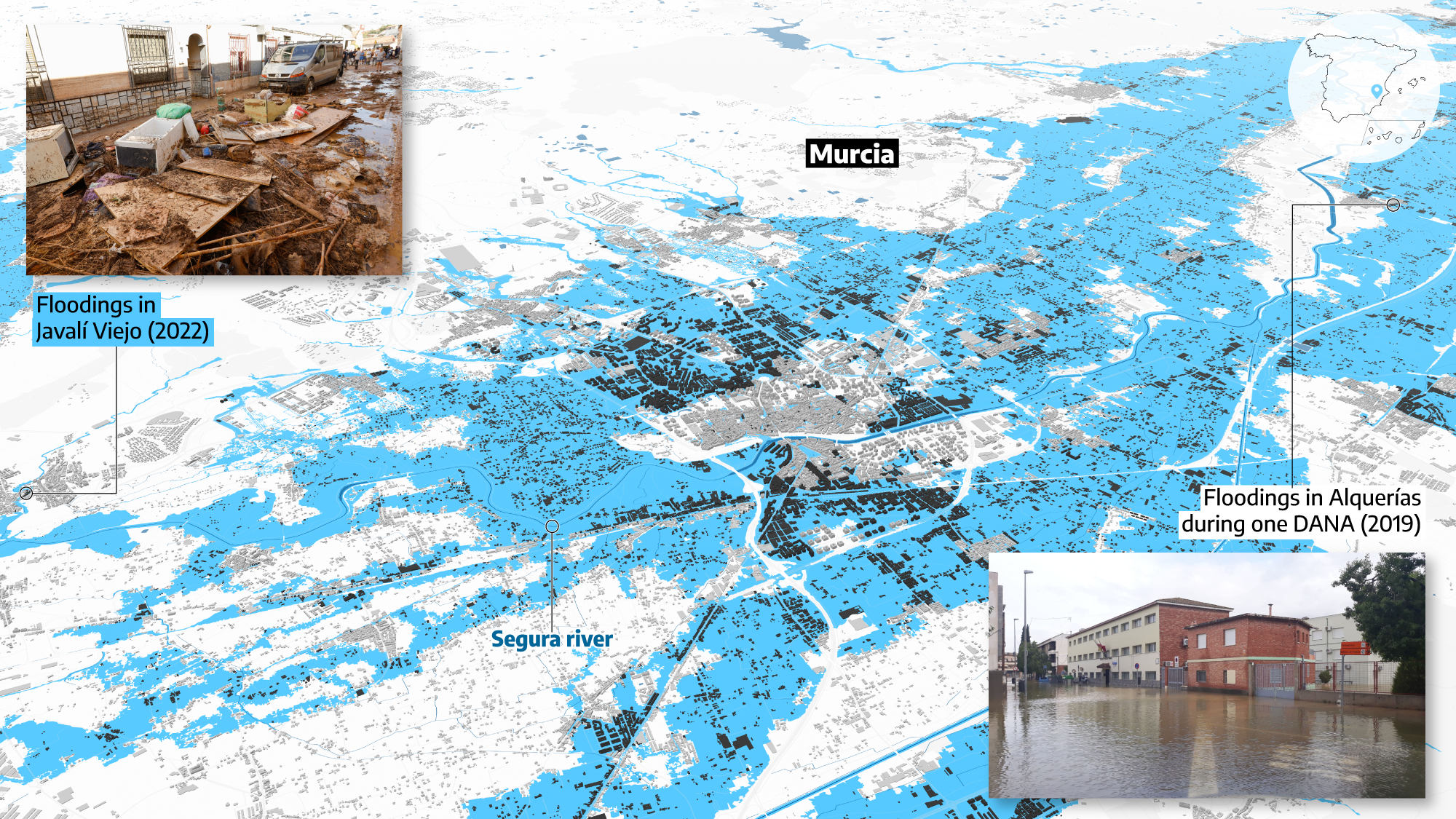

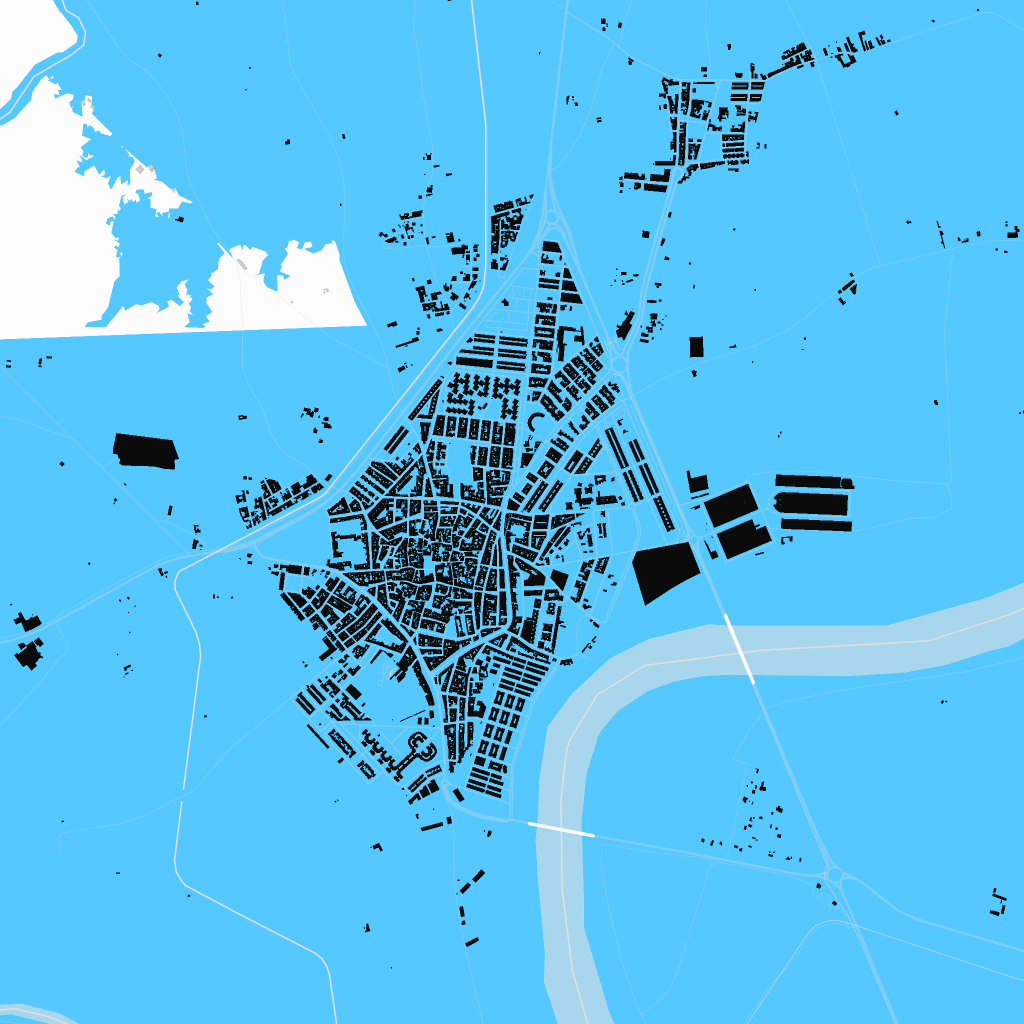

However, it is Murcia that stands out as the capital of the Spain at flood risk. According to calculations by elDiario.es, which use moderate probability of flooding as a reference, this city has the highest number of homes at risk. There are 60,775 homes, accounting for 28.6% of the total number of homes in the city. Historical records corroborate this fact: Murcia has experienced at least sixty episodes of serious flooding in the last hundred years and is the municipality with the most episodes of this type identified in the official records.

Right behind it, Valladolid, Palma, Girona, and Cartagena are the other large cities with more than 15,000 homes built in flood risk areas. In relative terms, around twenty towns stand out, such as La Algaba in Seville, Deltebre in Tarragona, and Santoña in Cantabria, where over 70% of their streets are located in flood risk areas. The highest record is shared by San Miguel del Pino in Valladolid, situated on the banks of the Duero river, and Alfara del Patriarca in Valencia, bordered by the Carraixet river. Both of them have 100% of their residents in at-risk areas. Across Spain, a total of 200 municipalities have more than one in five homes affected by this situation.

The regional ranking is led by the Region of Murcia (17% of homes affected), followed by Cantabria (10%), Asturias (9%) and the Balearic Islands (8%).

Regions with the highest number of homes at risk from flooding

Percentage of homes built in flood risk areas as a percentage of the total in each region

Source: Ministry of Ecological Transition, Cadaster

“There has been extensive construction near rivers in Spain,” says Ernest Bladé, professor at the School of Civil Engineering at the Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya (UPC) and director of the Flumen Institute. The so-called flood plains, plots of land adjacent to riverbeds, tend to be very attractive for urban development, explains Bladé. They are flat, and therefore it is easier to build or install communication infrastructures on them. “The problem is that as floods have historically been less frequent, we forgot about them and for years we built without taking them into consideration,” he explains.

In Alcanar, located on the coast of Tarragona, they are well aware of this situation. After 218 liters per square meter fell this Sunday, houses and businesses were flooded for the third time in five years. “In the past there was a misreading of urban planning, with buildings in the middle of ravines and riverbeds,” lamented the mayor of the town, Joan Roig, after the Llop ravine flooded and overflowed. Several episodes of torrential rains have left the town's finances in a “disastrous situation,” acknowledged the mayor.

Delimitation of flood risk areas, a calculation based on statistical, hydraulic models and geomorphological criteria, operates on a probability basis. The concept used is the return period in years; that is, the chances of suffering a flooding event on average every 10, 50, 100 or 500 years.

For this article, following criteria agreed upon by several experts, elDiario.es has chosen the 100-year return period. This means that all those areas are likely to experience (albeit not exactly) one flood or more during this period of time. “This is the standard in Europe, the one used by all countries to establish limitations on land use,” explains Francisco Javier Sánchez Martínez, deputy director general of Water Protection and Risk Management of the Ministry for Ecological Transition and Demographic Challenge.

Although this may seem like a vast window of time, it falls within the category of “medium or occasional probability”. And with the climate emergency, it could be reduced even further. In fact, the Administration technically considers a flood zone to be anywhere with a 500-year return period. If this last criterion were applied, and with ministerial estimates that only refer to the large river basins -the rivers that cross autonomous communities, such as the Tagus, the Ebro, or the Guadalquivir-, a total of 2.7 million Spaniards live in areas at risk of flooding. This accounts for 5.7% of the population.

In this regard, the fact that a building does not appear on the map does not mean that it is not exposed to risk. In fact, the calculation of at least one million homes in flood risk areas is conservative. Firstly, it does not include data from the Basque Country and Navarre, which have their own cadastral body. Secondly, it does not reflect a third type of flooding, in addition to river and sea flooding, which can also cause significant damage: pluvial flooding. These occur due to the simple accumulation of rainfall on land that cannot evacuate it (the most graphic example of this would be those that occur in underpasses in cities).

The consequences of floods

Video footage of different floods that occurred in the month of September between 2019 and 2022

Source: official videos from emergency services, Europa Press, EFE

The highest risk lies within the Preferential Flow Zones

After decades of scarce regulation on the matter, which has led to disorderly and excesive urbanization in flood-prone areas -especially along the coast-, in 2016 a new concept was introduced: the Preferential Flow Zones. These describe more enclosed areas that are not only flooded with water when there is a flood, but when it occurs it does with great intensity. Among the criteria considered is that the water exceeds one meter in height and that its speed is at least one meter per second for a 100-year return period.

“In the event of a flood, outside the preferential flow zones, what can happen is that the street and the house can fill up with 20 centimeters or half a meter of water, for example. But in a preferential flow zone, if you are walking down the street you may not even live to tell the tale,” explains Sánchez Martínez.

The difference is fundamental in terms of the consequences. Not all of flood-prone Spain is exposed to the same risk of serious damage, either to people or property. In some of the flood risk areas, the consequences of the floods may be minimal or non-existent, if the water accumulates in the streets and leaves without leaving any trace other than mud. In the Preferential Flow Zones, however, the effects become potentially serious, which is why the current regulation places much greater restrictions on the construction that can be carried out within their perimeters.

Unprecedented economic losses

In San Nicolás street in Javalí Viejo, all these data are tangible in terms of damage and lives. Isabel, whose house was completely destroyed, received 25,000 euros in insurance coverage. Josefa's house still smells damp, and more cracks are appearing on the wall every day, she explained. And then there is the fear: “Now when we see clouds, we get nervous”.

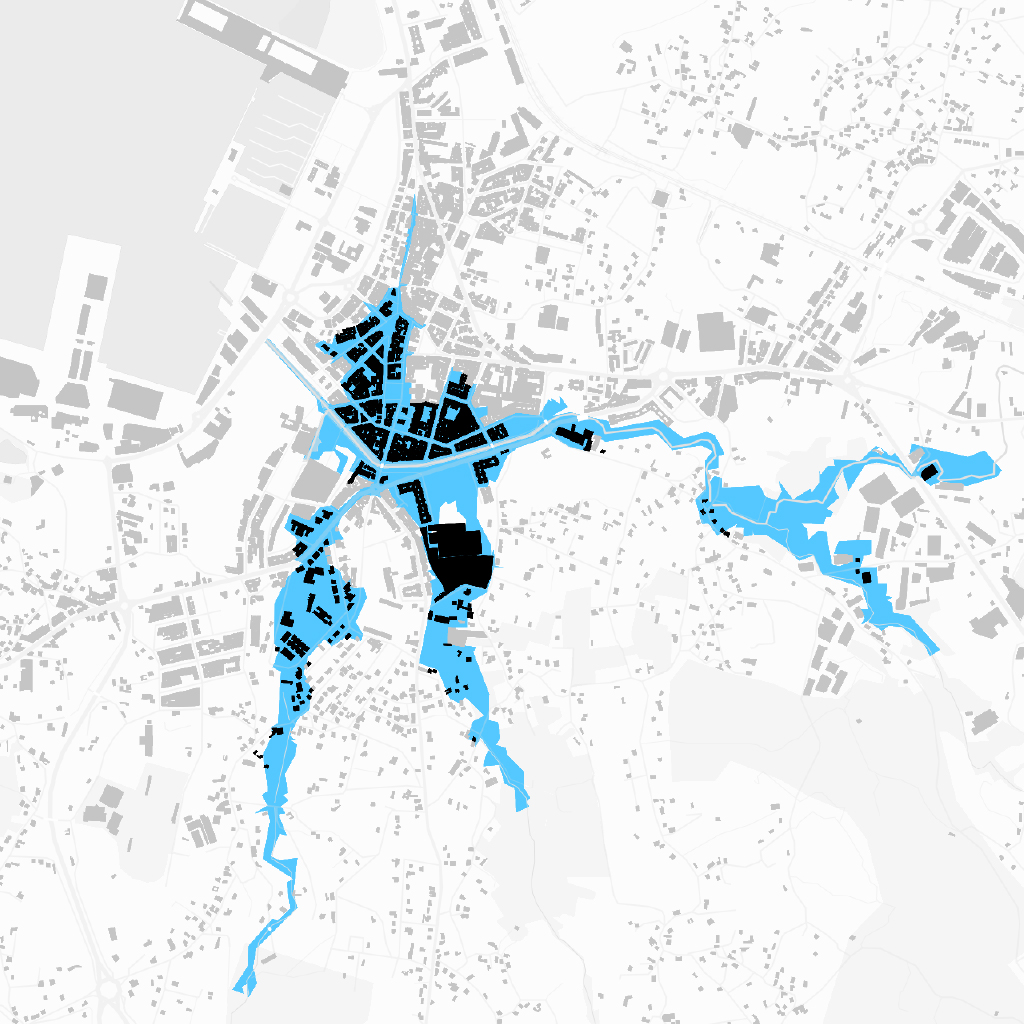

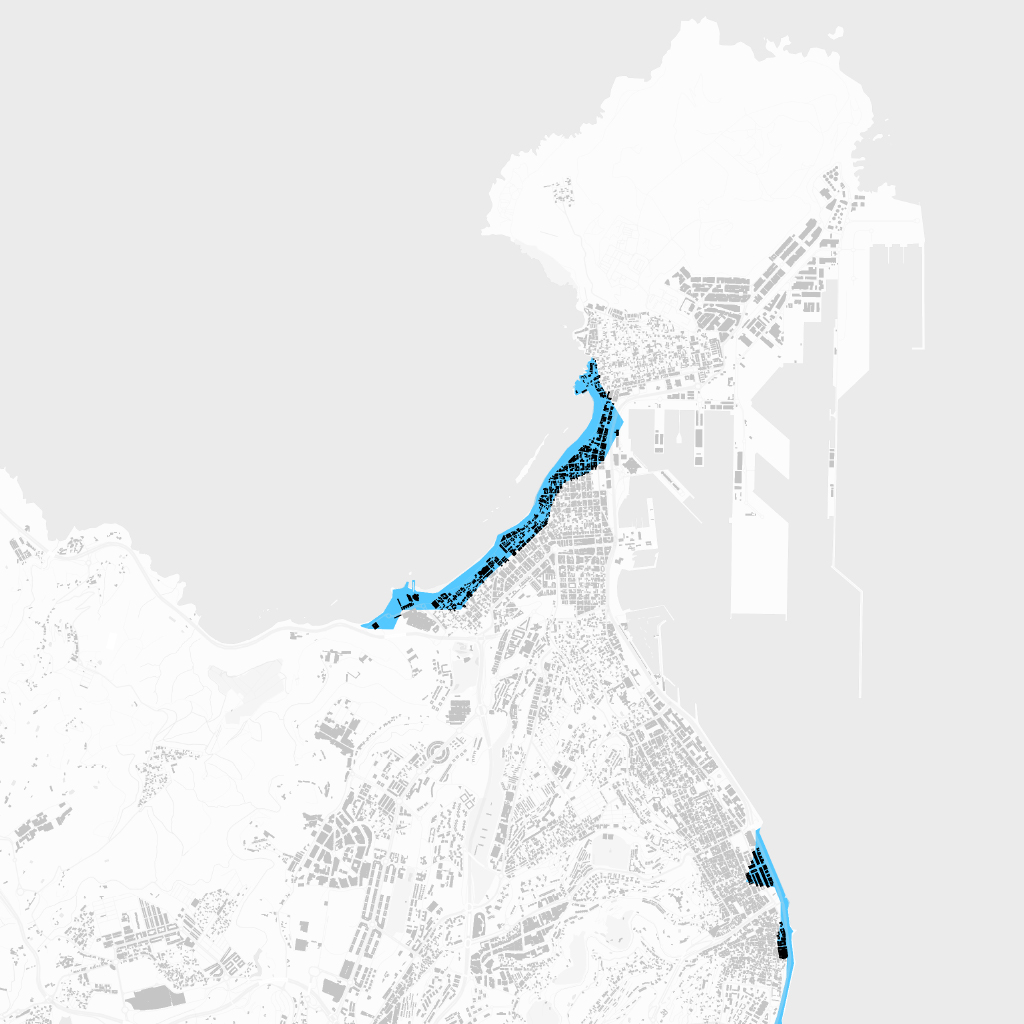

Murcia, flood-risk capital

Map of the areas of the city of Murcia that are at risk of flooding

Source: Ministry of Ecological Transition, Cadaster, Murcia Local Police, Europa Press

Floods are the most economically damaging natural phenomenon in Spain. Over the past 35 years, the Insurance Compensation Consortium has allocated a total of 7,251 million euros in compensation to victims of floods and torrential rains, with a particular incidence on the Mediterranean coast.

From the Costa Brava in Catalonia to the Costa del Sol in Andalusia, the Mediterranean coast is one of the regions considered to be at greatest risk in the future. It faces multiple challenges, primarily the fact that many beachfront developments are situated in flood-prone areas. Added to this is the rising sea level, already detected, which will increase in the coming decades due to rising temperatures, causing the beaches to continue to recede. And all this occurs alongo a heavily urbanized coastline -almost half of the it is covered in concrete and asphalt-, full of old streams, now dry, which can easily become rivers.

Every year, especially in the months of September and October, Eastern Spain experience recurring floods. In Lorca and Puerto Lumbreras, in Murcia, it is eleven years since the San Wenceslao flood killed five people in 2012. In the municipalities of the Mar Menor there are recurrent floods, with Los Alcázares serving as a stark symbol of this ongoing disaster. The town, crossed by three different ramblas or watercourses, has experienced half a dozen major floods in the last five years. To the point that there are neighbors looking to leave and some houses, when listed for sale, have to specify if they are in a flood zone.

The scale of the flood and sea storm hazards in the Region of Murcia has turned even the delineation of flood zones into a contentious political issue among government entities. The regional government has maintained an open dispute with the Confederación Hidrográfica del Segura (CHS), which depends on the Ministry for Ecological Transition and the Demographic Challenge, regarding these delineations. The release of new cartographic maps has resulted in the precautionary suspension of dozens of urban development projects that were planned in these areas, which has outraged several mayors and construction companies.

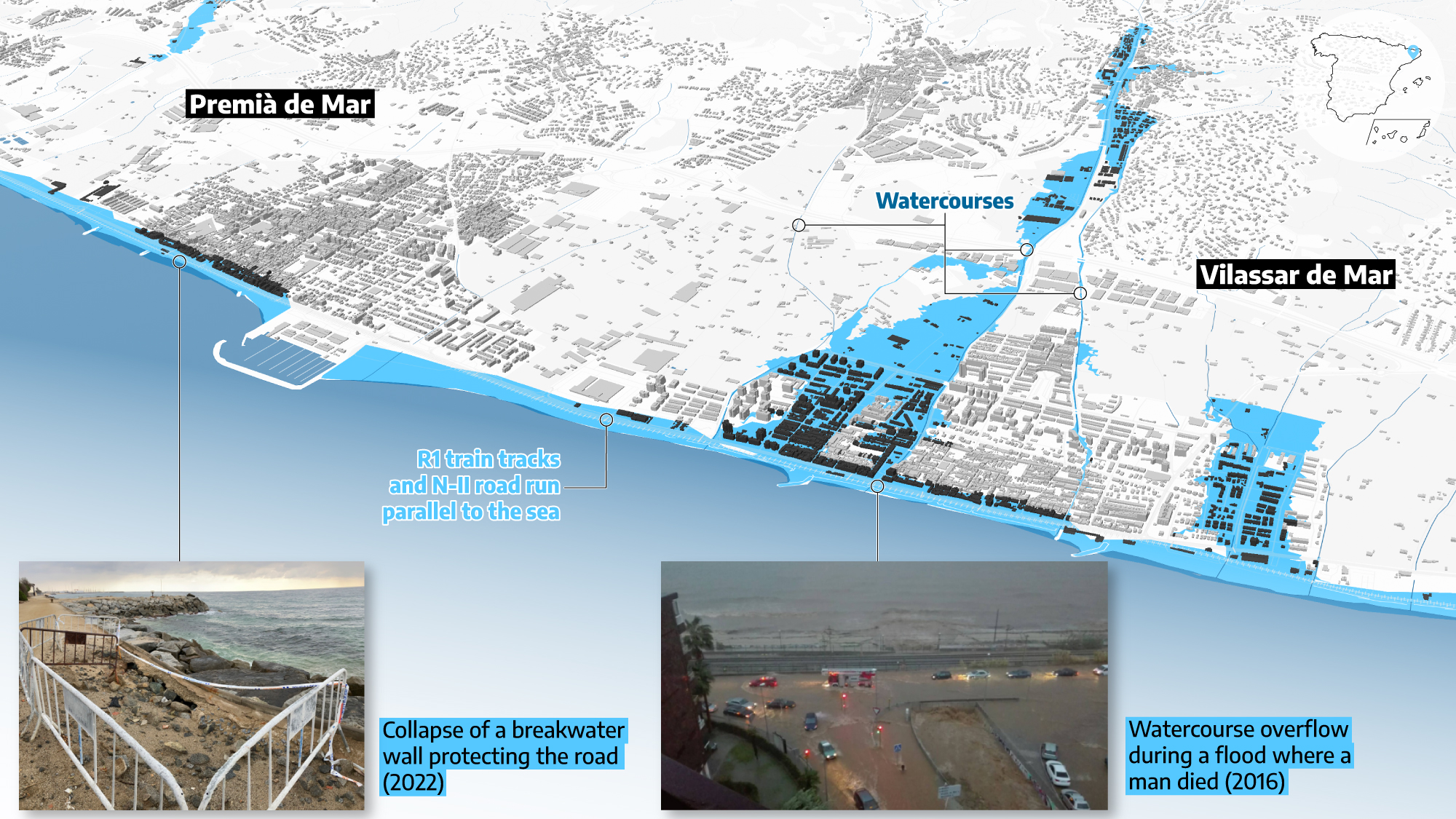

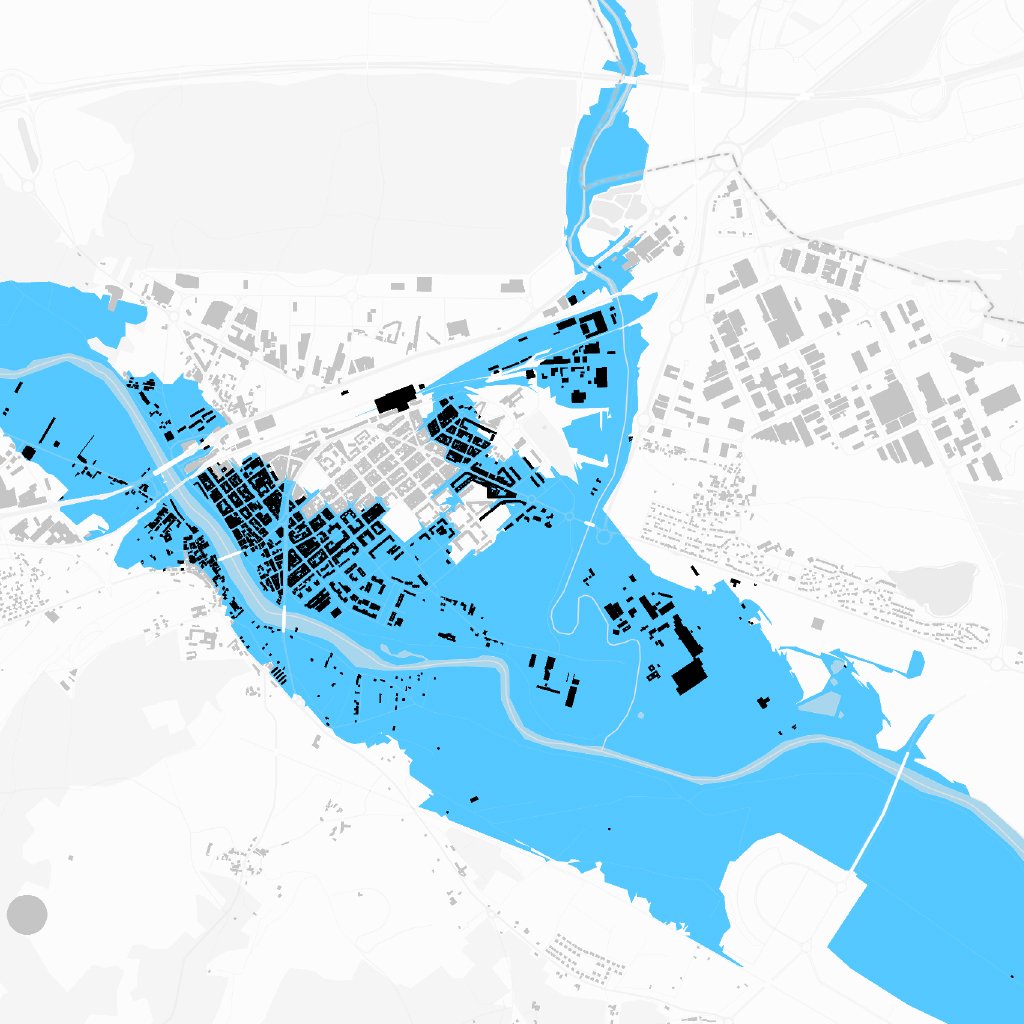

Waves are eating away at the oldest trainline

Further north, there's another area that also combines housing developments, dangerous watercourses and receding beaches: the Maresme region in Barcelona. In this case, what keeps their dozens of mayors and neighbors awake at night is the Rodalies R1 train line, used by over 100,000 passengers daily, most of them traveling to the Catalan capital to work or study. This railway is the heir of the historic railroad between Barcelona and Mataró, the oldest in the Iberian Peninsula, inaugurated in 1848.

Its tracks, along with the N-II road, run parallel to the sea, just a few meters away from the waves that are gaining ground on the beach year after year. Its current location is becoming increasingly unsustainable.

Joan Manuel Vilaplana, a geologist specializing in natural hazards with four decades of experience in the field, has a keen interest in this area. After every storm, he visits the area to take photographs and assess the impacts. He is clear about the future of the 50 kilometers of R1 railroad track and has been announcing it for years in reports and in meetings with politicians. “The space between the tracks and the N-II has to be dismantled and recovered so that the beach can be broadened, which is the best defense against flooding,” he argues. “Deconstruction is painful, but it is a national project with a 50-year outlook,” continues the current director of the GeoRisk Observatory of the College of Geologists of Catalonia.

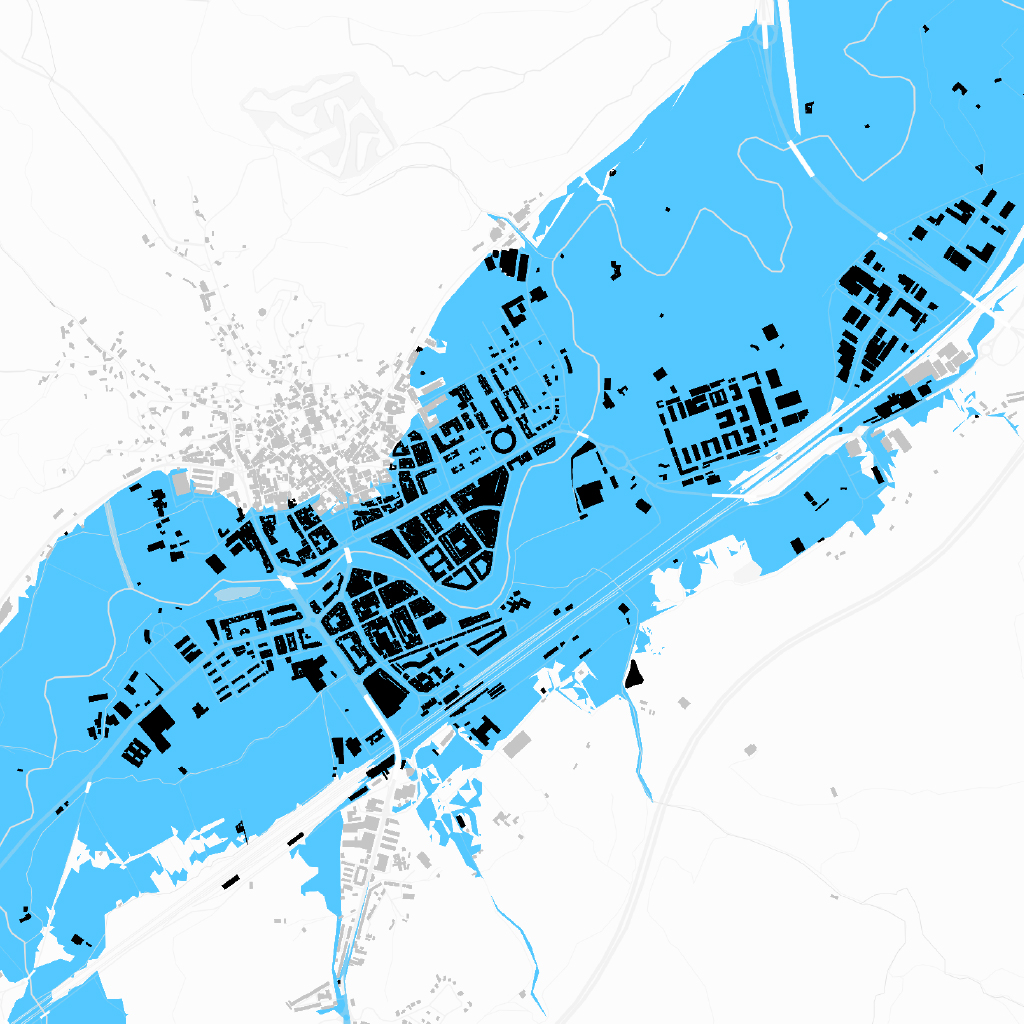

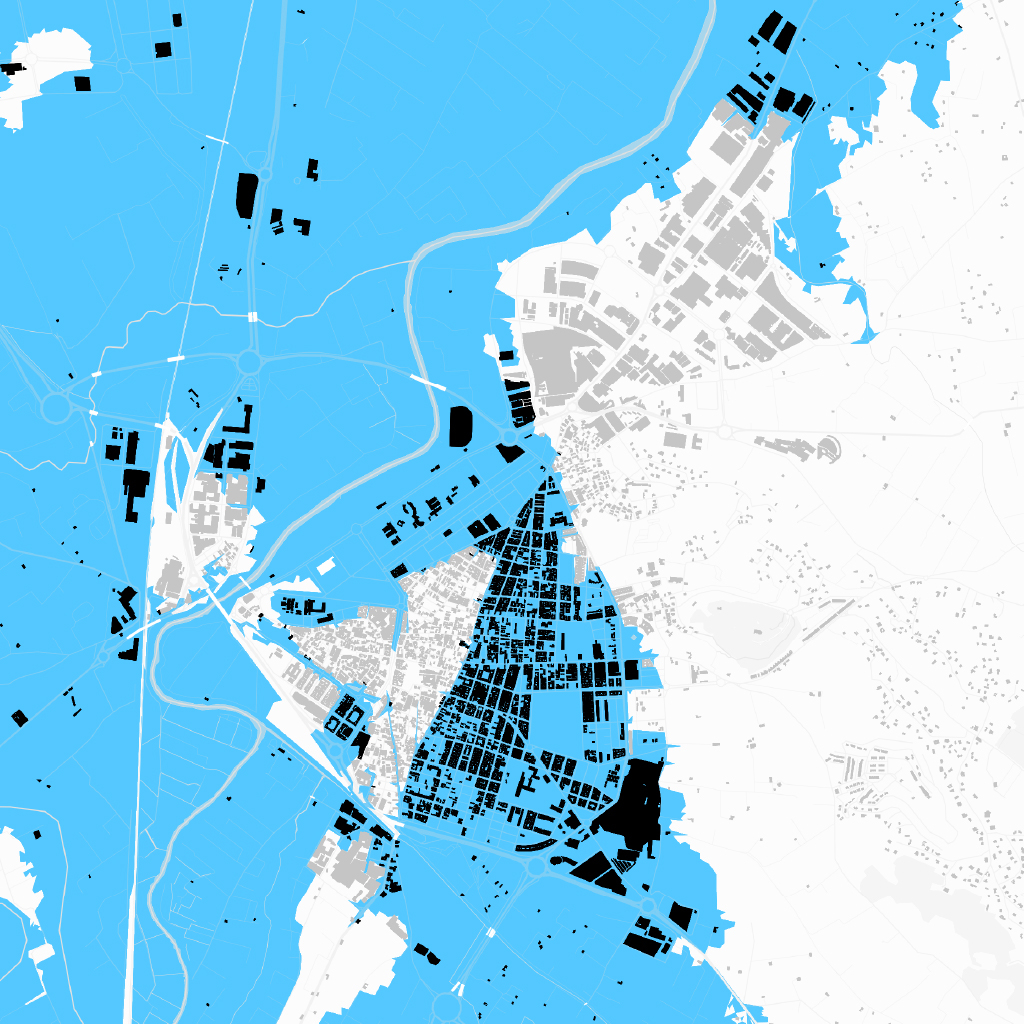

The train track on the verge of flooding

Map of the areas of these Maresme towns, in Barcelona, that are at risk of flooding

Source: Ministry of Ecological Transition, Cadaster

The relocation of this infrastructure has gained supporters over the decades but remains a distant dream. Adif, the Spanish state-owned railway infrastructure company, does not currenlty consider it, and in the meantime has spent millions of euros to improve the safety of the line, which still has to be interrupted often when there are storms. The most recent, storm Celia in 2022, caused a breach in one of the stone breakwaters that protect the route and the gap remains. Shortly after, another spectacular landslide left the waves less than a meter from the tracks between Pineda de Mar and Malgrat de Mar, an image that shocked travelers.

When inland rainfall is combined with storm surges, flooding is even more dangerous, adds Vilaplana. His solution to coexist with this natural phenomenon involves transforming the coastline. He put it on the table openly after the Gloria storm, when he called for the deconstruction of the coastline.

While walking between Premià de Mar and Vilassar de Mar, which is full of inhabited areas, old and modern, Vilaplana’s diagnosis is extremely blunt: “We have been short-sighted, irresponsible. People knew the effects of the floods and yet the municipalities authorized planning permission in flood zones. A huge irresponsibility was committed, I am telling you,” he says.

In Premià de Mar, 5% of the houses are located in flood risk areas, according to data compiled by elDiario.es. In Vilassar, the figure rises to 25%.

Before and after Biescas

It wasn't until the catastrophic event in the town of Biescas in Huesca, where a flood killed 87 people who were staying at the Las Nieves campsite, that the local authorities began taking action in terms of urbanization and flood prevention. That flood was the second deadliest in the recent history of Spain, after the one that devastated the Vallès region of Barcelona and left hundreds of people dead in 1962. The Biescas tragedy occurred in 1996. “That was a before and after in terms of flood prevention,” acknowledged the deputy director general of Water Protection and Risk Management and the other experts consulted.

Before that tragedy, the regulation of flood-prone areas in Spain was like a puzzle, says Sánchez Martínez. “Some regions assumed responsibility, such as Catalonia, the Valencian Community, the Basque Country and Navarre, while others turned a blind eye. In Spain there were those who thought that it was the responsibility of the communities, as it was land use and urban planning, and there were communities that said that it was the responsibility of the state, because it was a natural hazard,” explains Sánchez Martínez.

Another decisive moment was the enforcement of European regulations in 2007, to which successive modifications of Spanish regulations on the public water domain were adapted. Since then, experts note, building in flood risk areas has become more complex and urban and architectural prevention requirements must be met, such as raising the land or erecting retaining walls. Especially since 2016 in the so-called Preferential Flow Zones. “But none of this was regulated before. Decisions were made based on human memory and that is very short,” insists engineer Ernest Bladé.

Nestled between the Guadalquivir and Rivera de Huelva rivers, few municipalities know what it is like to live with floods like the Seville town of La Algaba does. Ninety-nine percent of its homes are in flood-prone areas. “Here, no construction is authorized until we have the water report,” explains the Councilor for Urban Planning and Management, José Manuel Gutiérrez. “The town stays where it is,” he insists. Locals remember with nostalgia the number of times they had to evacuate by boat during river floods. A special mention must be made of what is known as the Old Bridge Tragedy, in 1924, when the infrastructure that crosses the Guadalquivir River collapsed with 200 people on it. Fifteen people died.

A century later, in La Algaba, every inch of land that is urbanized is analyzed. The last major flood, in 2010, flooded only two kilometers of orange groves near the village. “When building a new house, there are geotechnical studies that indicate where the water table is, what type of soil there is and what type of foundation or waterproofing is most suitable,” the town council reports.

Cities have employed diverse strategies to combat and mitigate floods, and the effectiveness of these measures has improved over time. Besides the capital importance of reservoirs in this task - one of the main tools for flood management - there are also dams, rainwater tanks in cities, sewerage improvements, channeling projects -such as the pharaonic diversion of the Turia in Valencia after a flood that left a hundred dead in 1957-, waterproofing of farms. But some urbanizations are also being reconsidered.

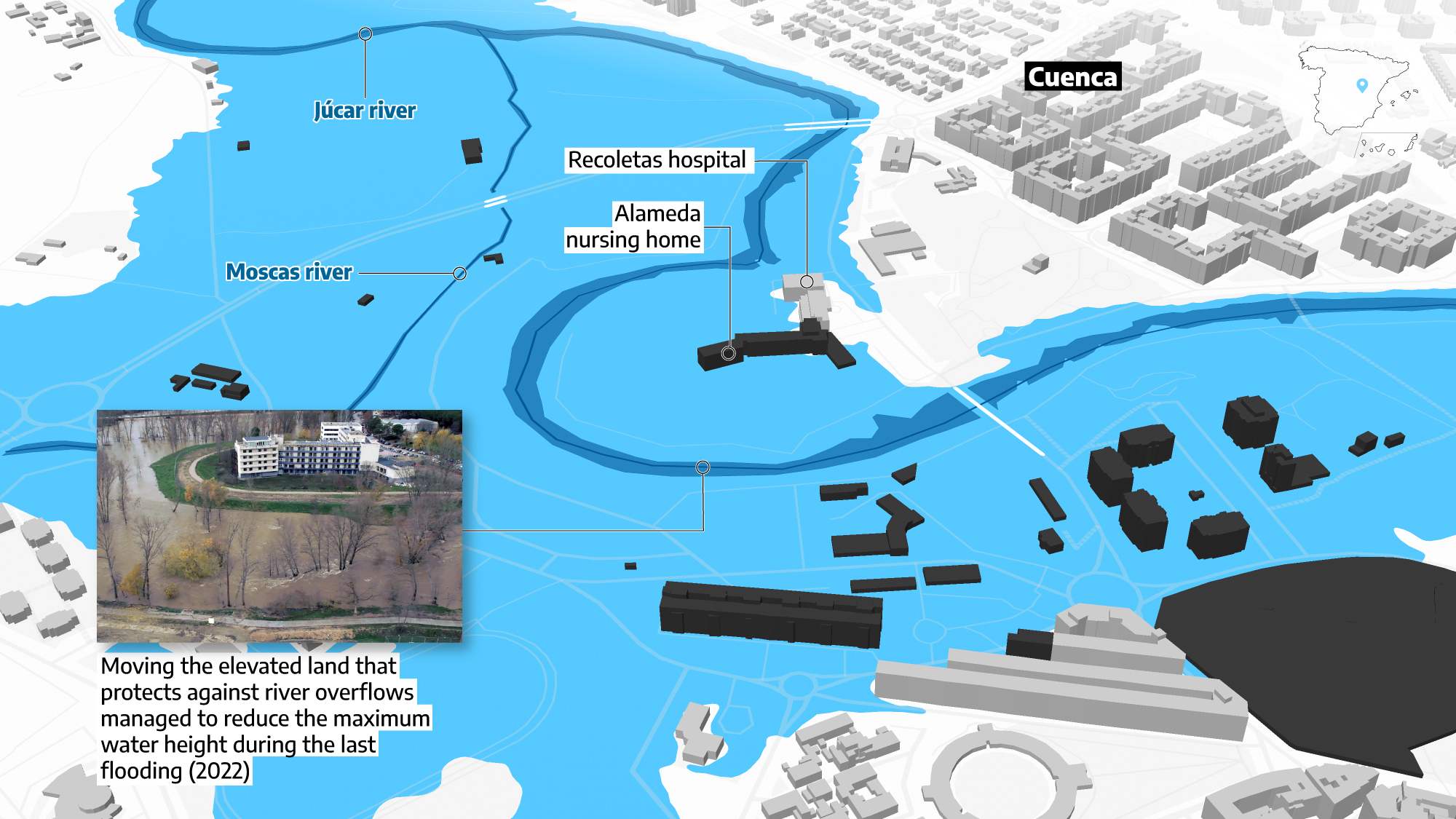

In Salou, the City Council has demolished 29 houses in the Barenys ravine area, which features regularly in the Catalan news when there is flooding, in order to channel a torrent. In the Basque Country, the government is working on several projects in flood-prone areas, including the raising of several bridges in Guipúzcoa to prevent them from getting blocked when the river level rises. In Cuenca, for example, they invested two million euros to naturalize the area around the Recoletas hospital and the Alameda nursing home to prevent flooding when the Júcar river rises.

Service buildings in flood-prone areas

Map of some of the city of Murcia areas that are at risk of flooding

Source: Ministry of Ecological Transition, Cadaster, Confederación Hidrográfica del Júcar

Most of the actions currently being undertaken by authorities, often funded by European Next Generation funds, are related to the warnings that the climate emergency will result in more violent episodes of torrential rains such as those derived from the DANAs. Unlike temperatures, which scientific consensus agrees are clearly rising, rainfall predictions are not so accurate. Amid an unprecedented drought in Spain, it may seem paradoxical to speak of more and more servere floods. But what organizations such as the UN - and its panel of climate emergency experts, the IPCC - do point out is that there will be more extreme episodes of rainfall, with heavy downpours in just a few hours.

“What is expected is that storms of a short duration will be increasingly intense, and this will clearly affect eastern Spain,” says Luis Mediero, an engineer specializing in hydrology at the Universidad Politécnica de Madrid (UPM). These areas are abundant in dry watercourses and streams that overflow during torrential rains.

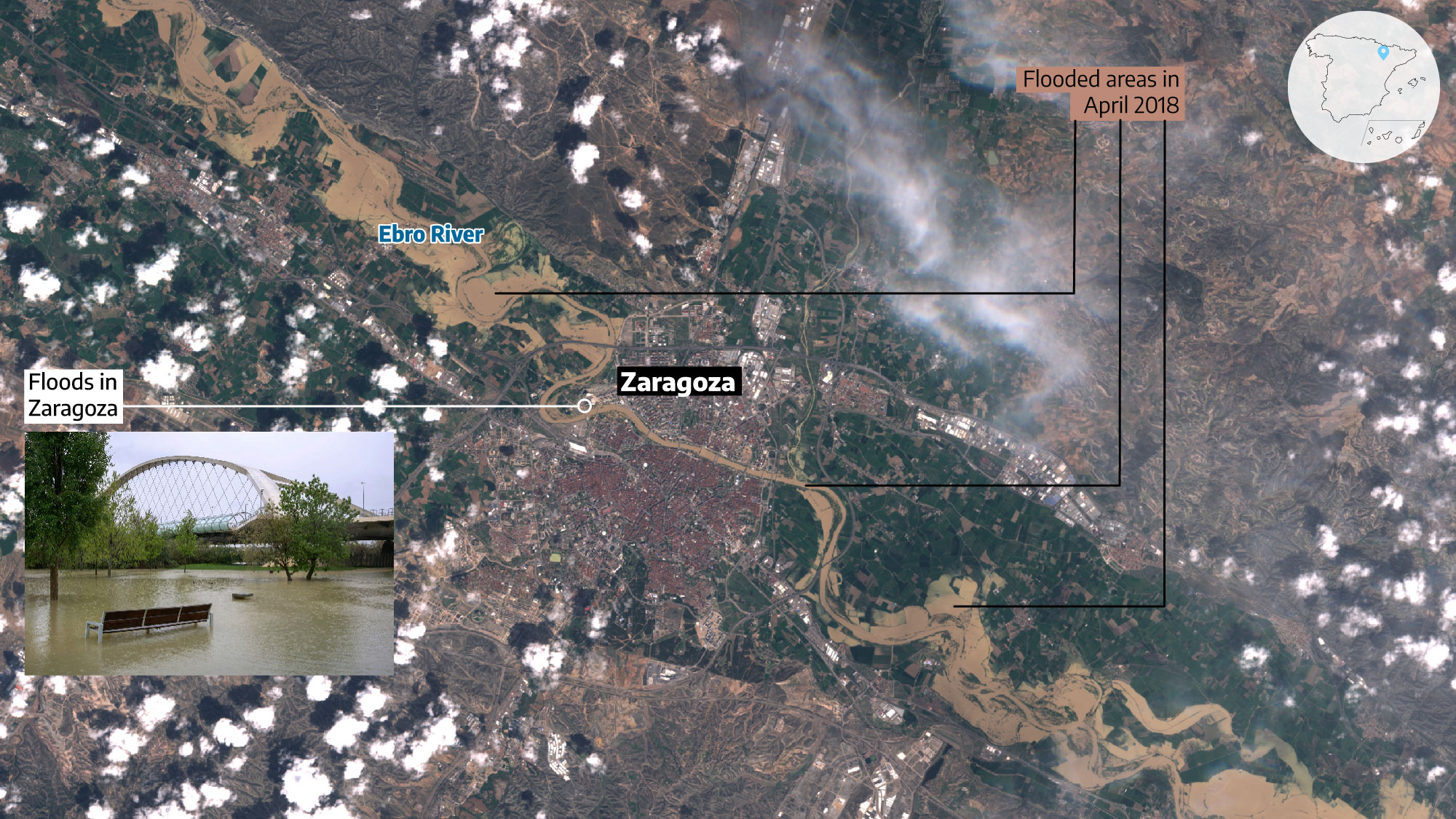

The Ministry also warns about other factors that could exacerbate flooding, aside from sudden and intense rainfall events. One of them is the faster melting of snow in the Pyrenees, especially significant in the Ebro basin. “This is a top priority because of the amount of damage that can occur, and we are already beginning to see the effects of climate change,” says Sánchez Martínez.

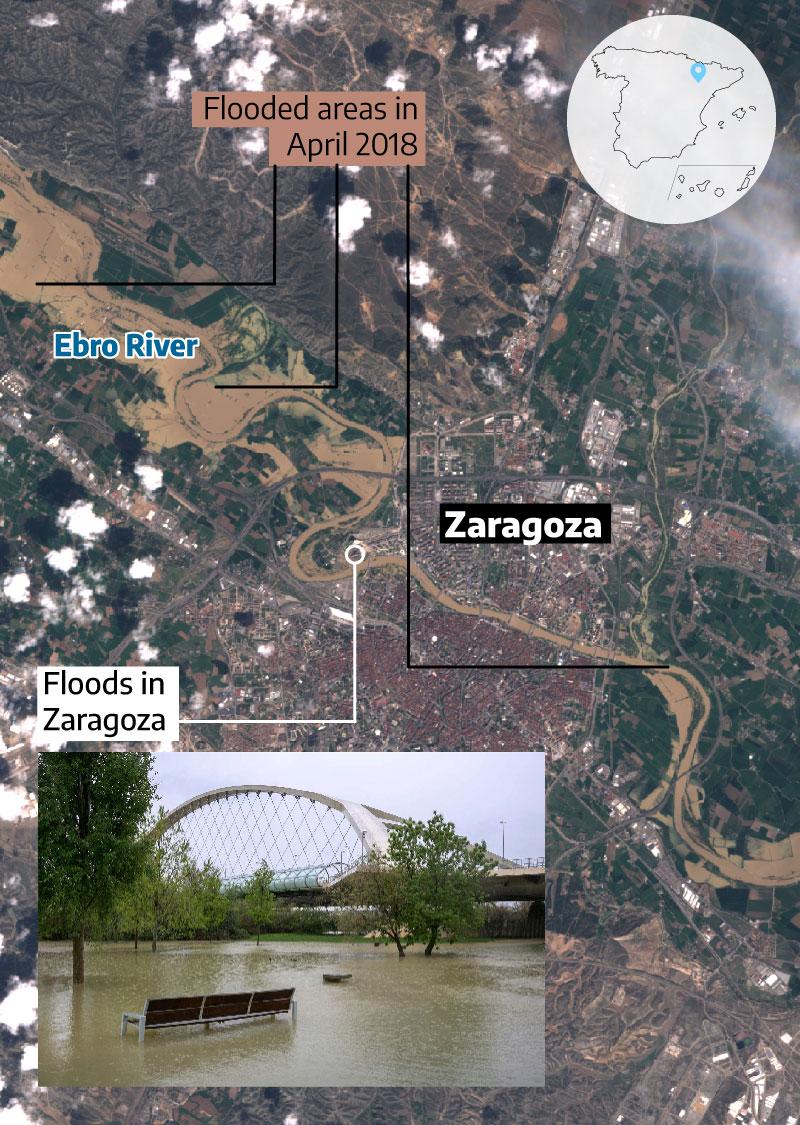

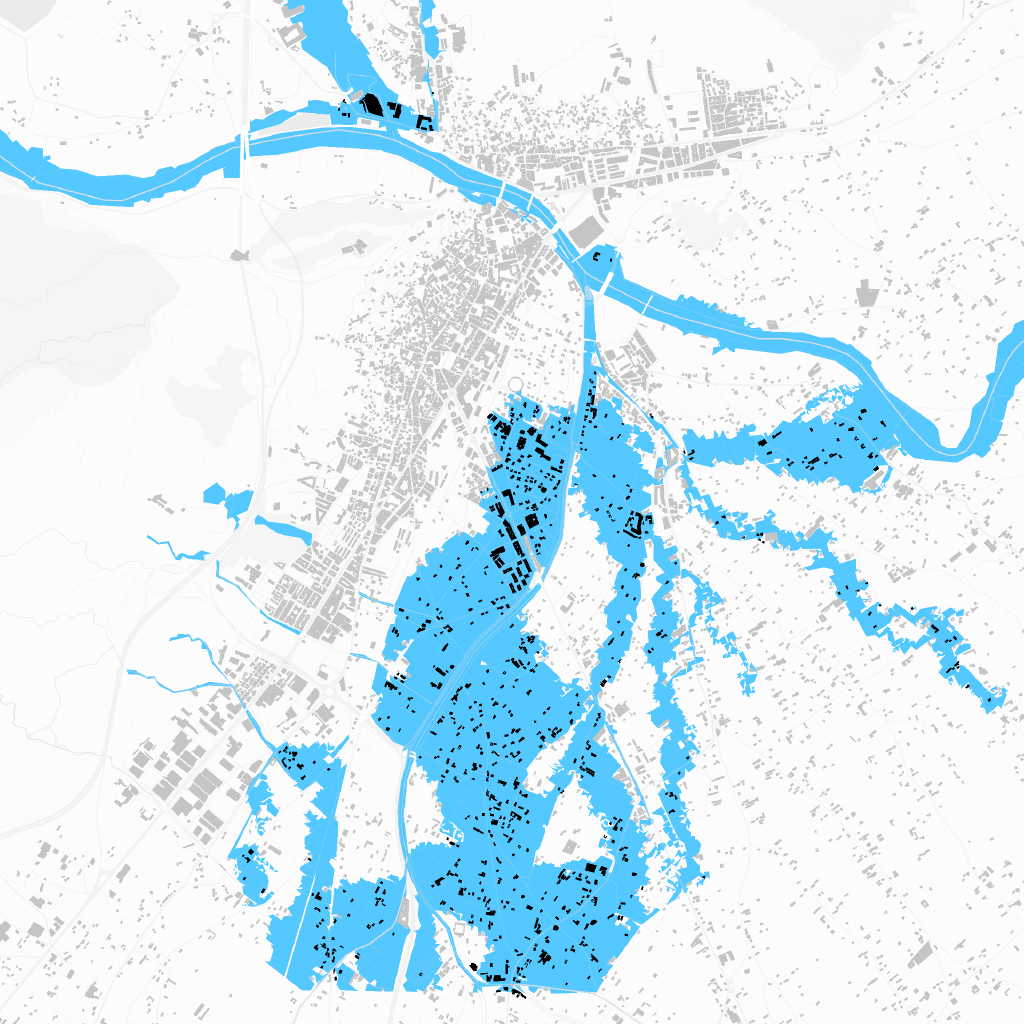

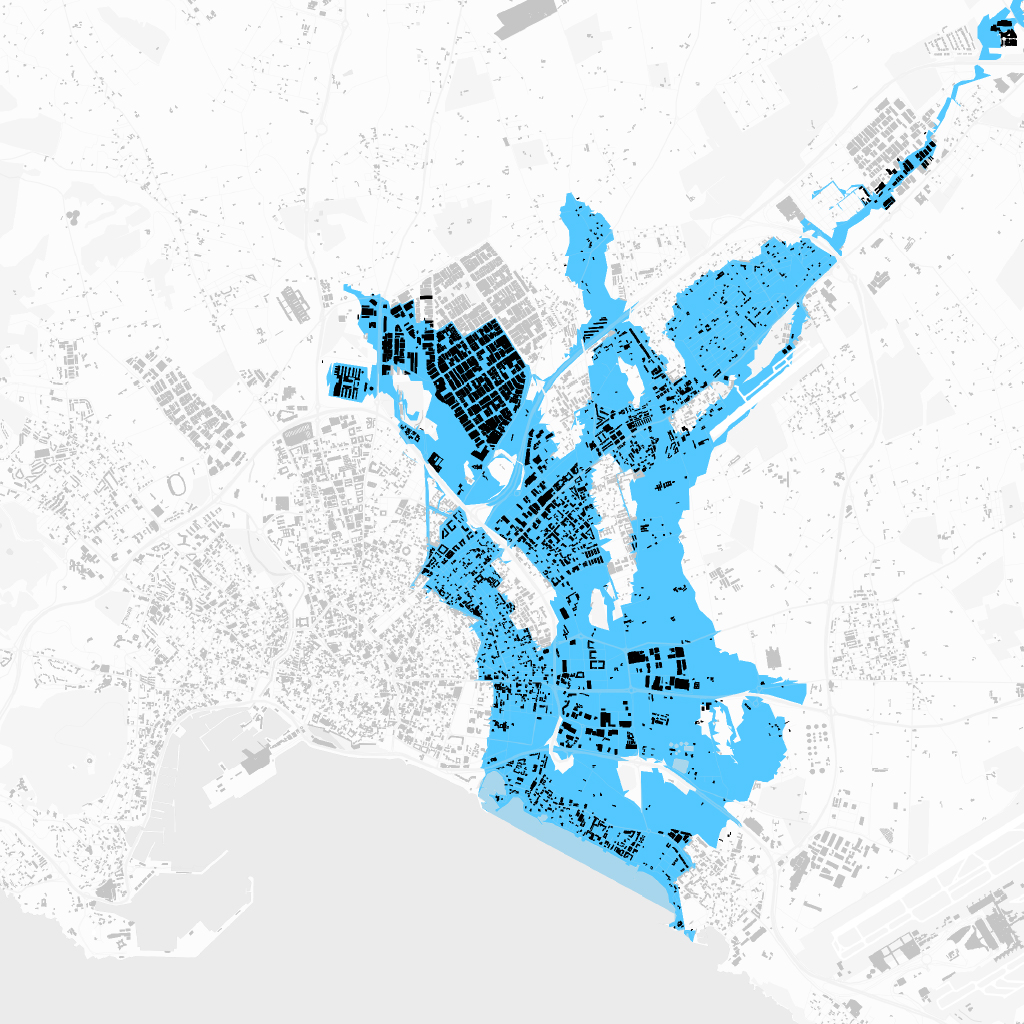

While satellite photographs are challenging to obtain during floods due to cloudy skies, images from the Copernicus system obtained by elDiario.es corroborate that the areas affected by recent floods largely coincide with the boundaries outlined by the National Floodplain Mapping System. This was evident in the case of the Ebro flood in 2018, for example.

The flooding of the Ebro River

Satellite images of the floods in Zaragoza in April 2018

Source: Ministry of Ecological Transition, Copernicus, EFE photo (Javier Cebollada)

And another aspect to consider in the face of the climate emergency is the desertification of river basins. Due tu increasing heat and wildfires, riverbeds are becoming drier and drier, resulting in soil becoming less structured and more impermeable during heavy rainfall, leading to reduced water absorption.

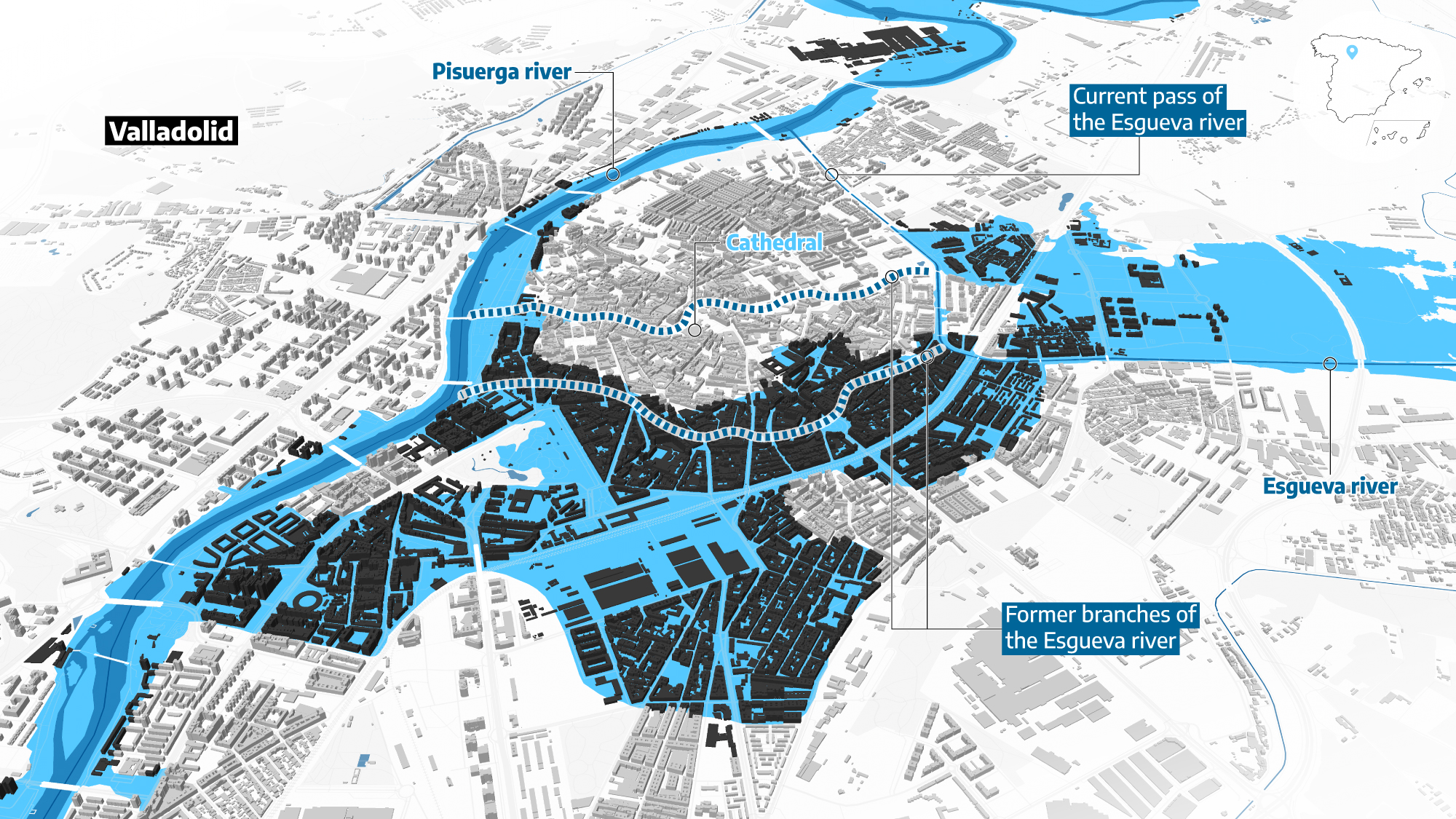

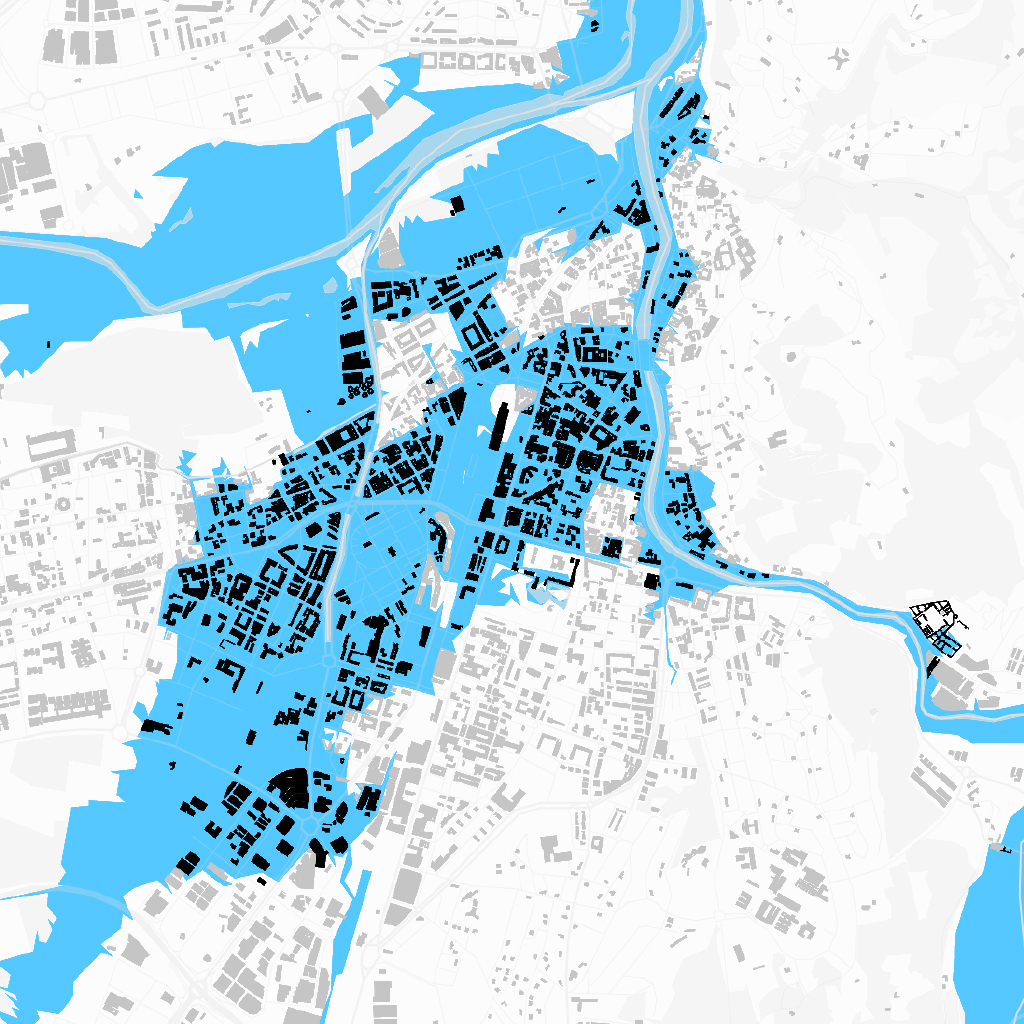

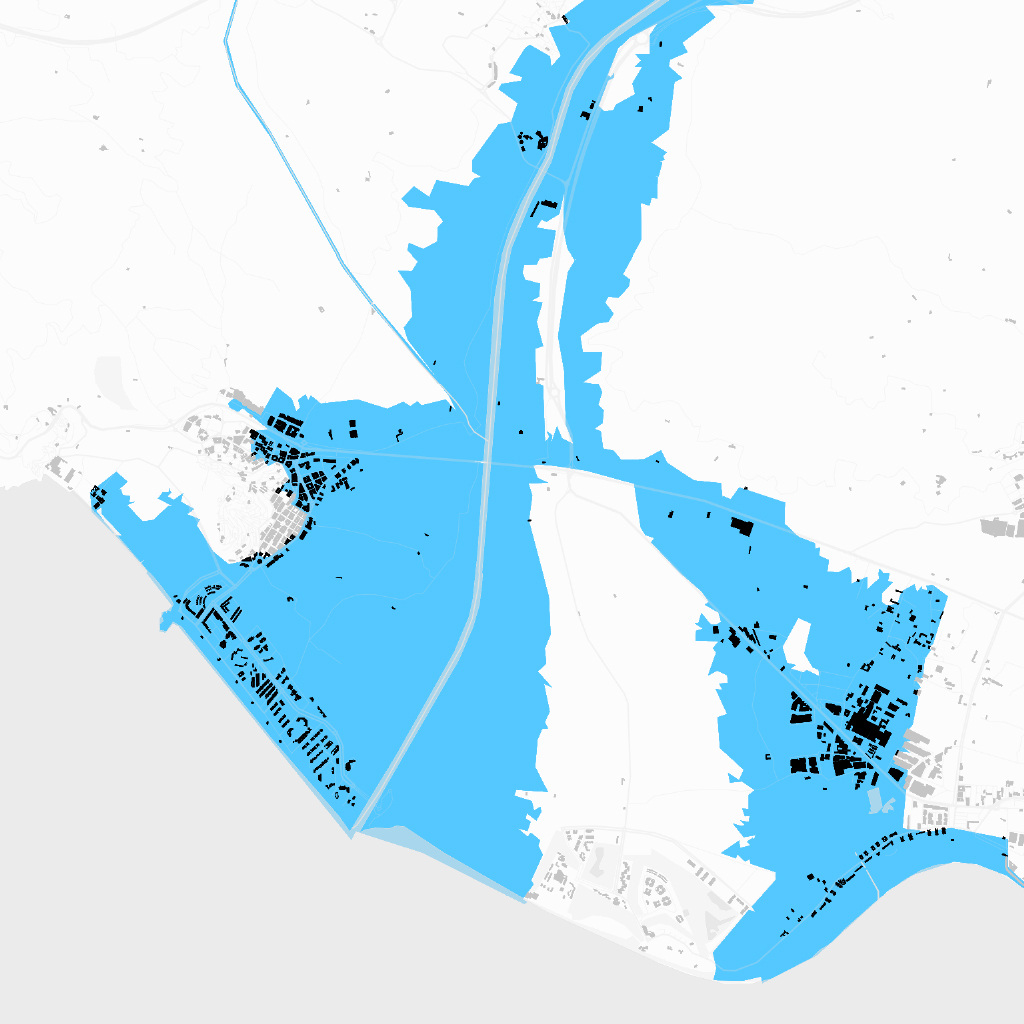

One rainfed city with a history of flooding is Valladolid, which according to the data analyzed for this report has 46,888 homes at risk of flooding, 30% of the city. This is not because the Pisuerga, its best-known river, runs through it. The most serious floods recorded in the city are linked to the branches of the Esgueva river, one of which was channeled in the 19th century. “The Esgueva has always been feared here,” explains historian Jesús Anta. The most destructive flood in the city occurred in 1636. It killed a hundred people.

In the 20th century, Anta recalls the New Year's Eve 1961 when a storm caused the Pisuerga river to overflow its banks. In 1978, the Esgueva was on the verge of overflowing because the floodgates were closed, and it was impossible to open them. “The army had to go in with the explosive goma-2 to try and blow it up and they caused more damage from the explosion and broken glass in Barrio España than anything else.” Forty years later, in 2019, some streets began to 'inexplicably' fill with water during a storm. Among them, Platería, where the Esgueva used to flow. Ana and Carmen, who run a tea store there, remember that day. “The water was up to our ankles, but it got into our storeroom, because the shop is on a slope... We were without electricity,” they explain.

Danger in the old pass of the Esgueva river

Map of the areas of the city of Valladolid that are at risk of flooding

Source: Ministry of Ecological Transition, Cadaster

Danger at the old Esgueva river crossing

Floods may last only minutes, but their consequences take a long time to disappear. In Javalí Viejo they are well aware of this. The water goes away and so begins the bureaucratic ordeal to receive aid. The City Council of Murcia has processed 25 requests. “They are the only ones we have received so far, 5,000 euros from the social workers and 600 from Caritas,” complains Josefa. “We have not even seen President López Miras pay us a visit; he should come to our neighborhood and see what our real situation is, it is dramatic”.

Isabel, who lost her house in the flood, couldn't even save her ID card. “Only a photo from my communion that was in the living room up high.” A friend of Antonio's, she now considers what had never crossed her mind before, leaving the neighborhood: “I have lived here all my life, and I have always had a lot of respect for the watercourse, but I never imagined that this could happen”.

How many houses in your municipality are situated in flood risk areas? In the following search engine, you can find all the municipalities with houses built on areas at medium risk of flooding. You can see the number of houses that are in this situation and the percentage they represent of the total.

Translated by Emma Reverter. This story has been elaborated with the collaboration of Erena Calvo (Murcia), Alba Camazón (Valladolid) and Ana Ordaz (Seville). David Velasco has collaborated in the editorial design of the project and the video editing is by Nando Ochando and Clara Rodríguez.

INVESTIGATION | Spain at flood risk

_________________

The planet at a critical juncture

Floods, wildfires, drought, record temperatures... The climate crisis is the greatest challenge faced by humanity. Extreme weather events are becoming more and more frequent as a result of human activity. To explain this complex reality, and its enormous social, political, and economic repercussions, we need journalism that is faithful to the facts and independent of major corporate interests.

Fighting climate denialism and informing about the issue of pollution and emissions, the deterioration of natural spaces, the extinction of species and initiatives in favor of the environment is urgent.

If you care about the future of the planet, support us. Today we need you more than ever because our work is more necessary than ever. Become a member or a supporter of elDiario.es.

0